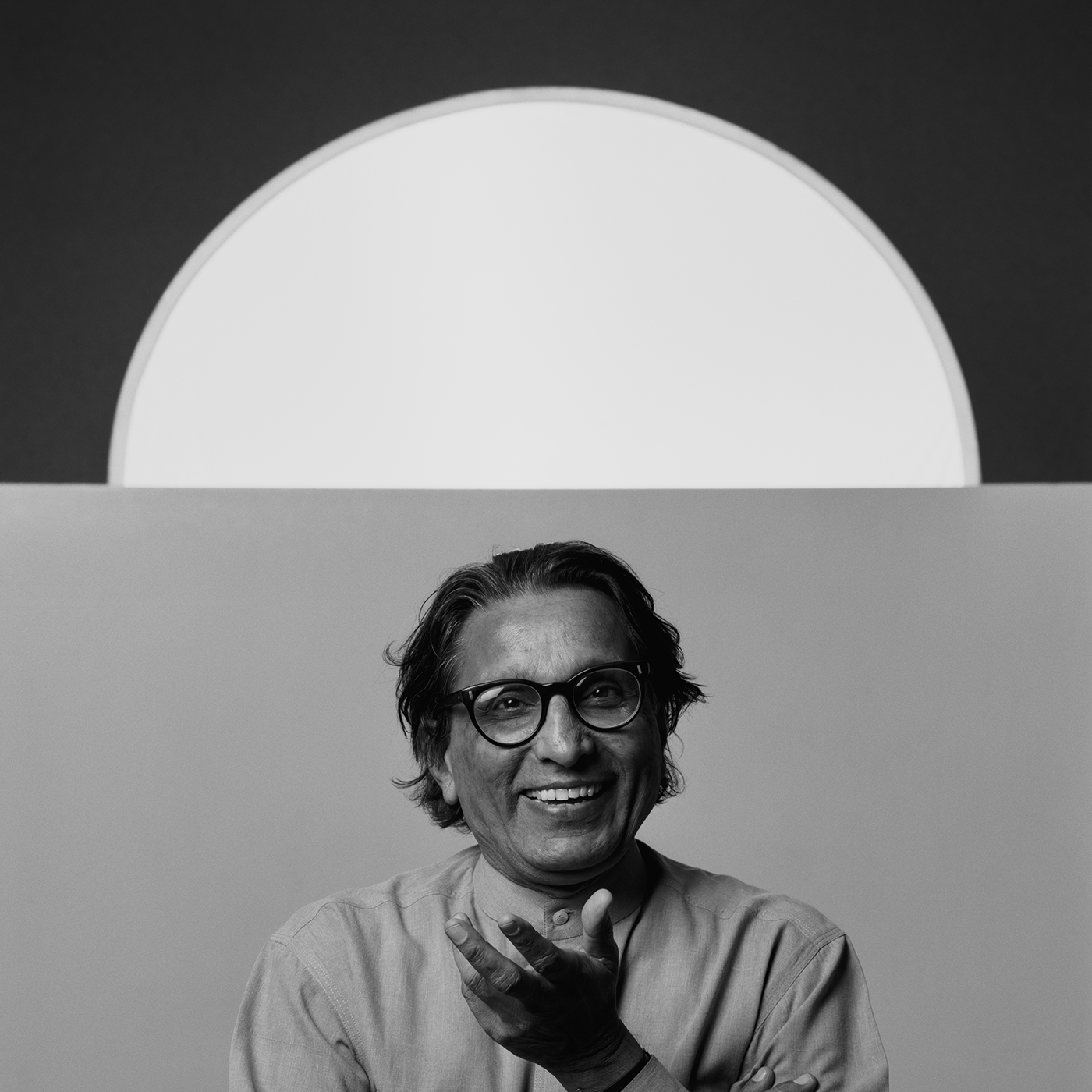

photo Luca Vignelli

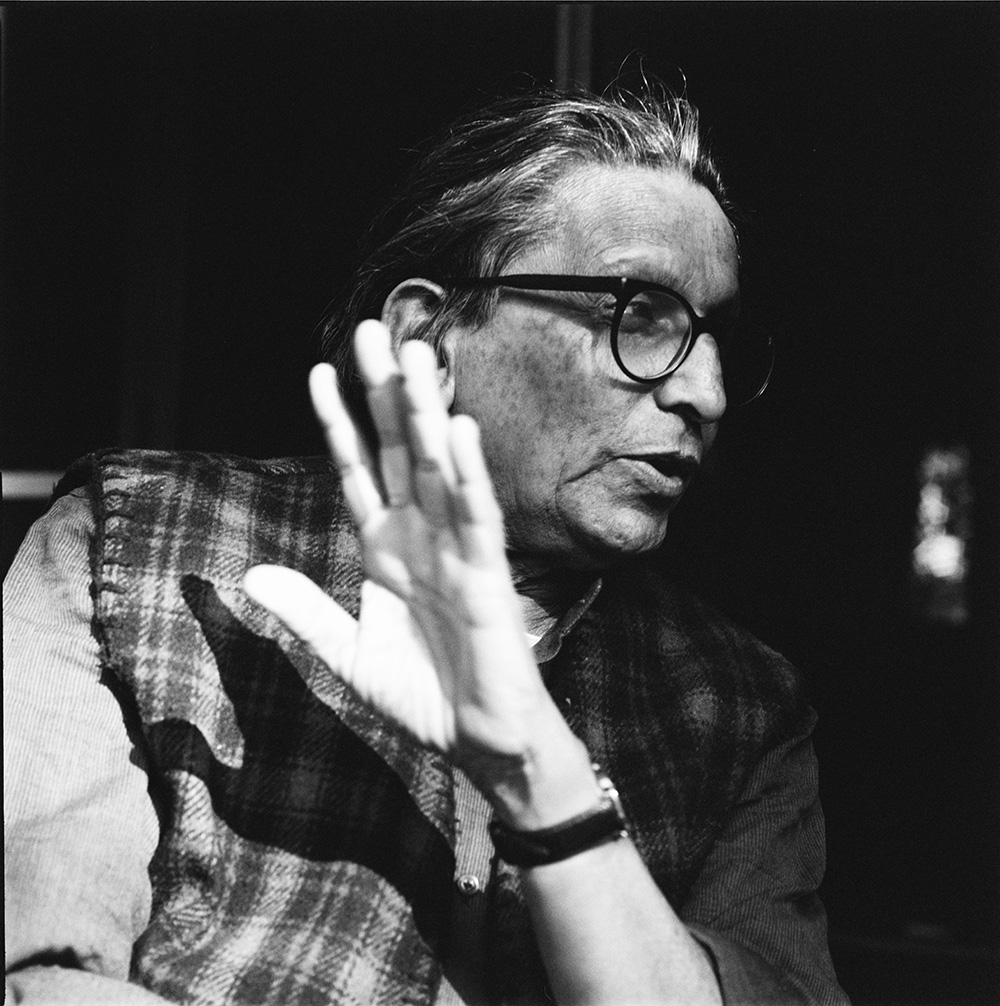

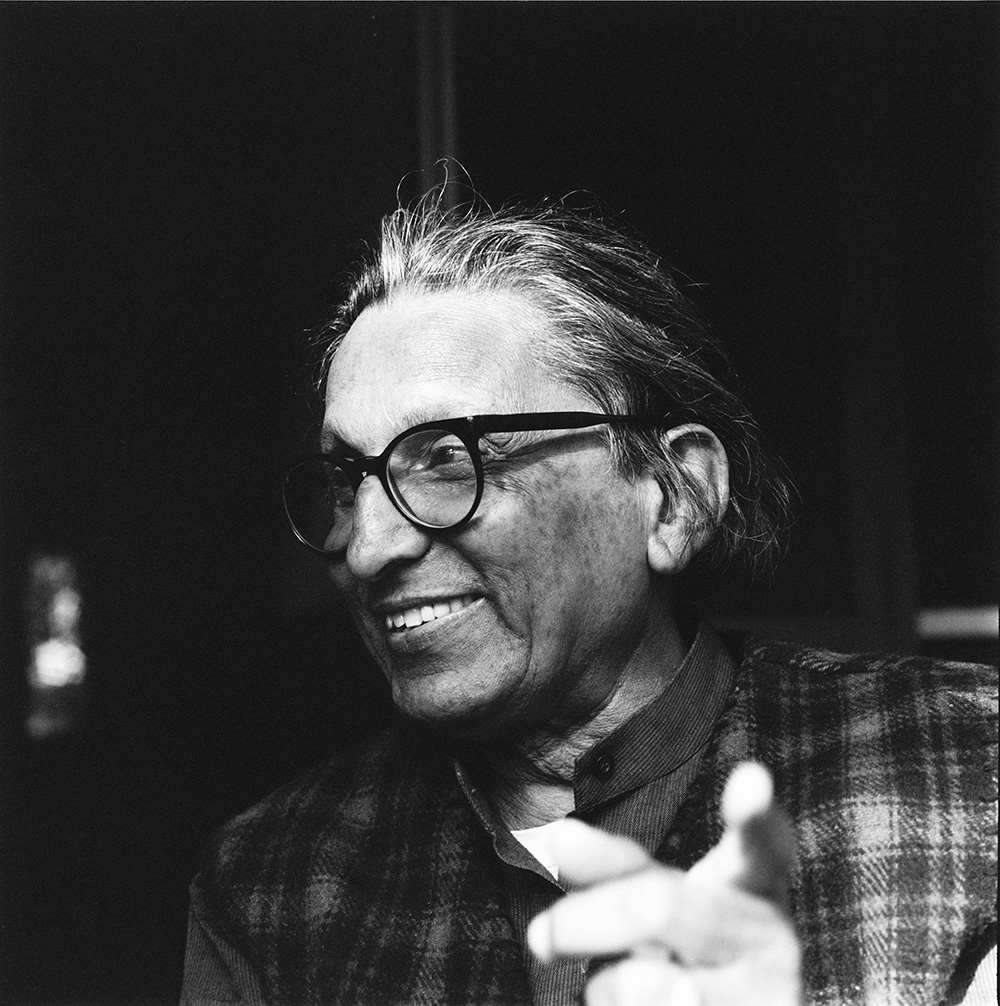

January 24 morning Balkrishna V. DOSHI passed away to his loved and lovers, to the whole world. I want to re-cord at the time of his death his legacy of vitality.

The spirit has left the body, but it will remain present in those of us who have crossed his gaze, have been caressed by his words but especially it will be reborn again and again in those who will explore his figure and the testimonies of his doing. So much has been said and written but so much more will be written because Doshi is a spring.

To him I owe the landing to a vision of architecture as a habitat construction, a theatre of experience, a vital and living space when fully experienced between spirit (of places and time and self) and body (individual and collective, social and environmental).

To have known and loved him was a gift for which I will never cease to give thanks. We met by accident on my first trip to India, but the coincidence never comes by chance (I recounted this in an article published in Casa Vogue and then in ArtTribune ). An incomprehensibly deep and solid thread tied us together, irreducible to the dimension of teacher, mentor, father, he was much more, the only one who really managed to caress my soul and radically change the course of my life by introducing me to inner silence and to meditation, to the discipline of acceptance and receiving.

After the first trip in 1993 followed many others, once year and sometimes twice. As many were Doshi’s visits to Italy, always with some member of a family that welcomed me, adopted me and of which I feel a part. The first time we drove across Italy by car from Venice to Sicily, with an intermediate stop to say hello to Leo Lionni (to the sonorous assonance of our last names I owe the meeting with Doshi) in Tuscany, where he had a home and that time, he painted the Palio of Siena “cencio”. Then we reunited with other family members who had stopped in Florence and Rome, toured Sicily by van singing in Gujarati and Sicilian, familiarising…

Given that architecture is influenced by life and influences life (as neuroscience research confirms) and considering that architecture is the art of modifying the environment for habitation, the architect has definite ethical and social responsibilities. Their work can affect the well-being of individuals, society, and the environment. Doshi was well conscious of this. The uniqueness of places, the plurality of dwelling and the universality of forms converge as concentric trajectories in the awareness that every event trigger changes near or far, direct, or indirect; thus, the connection between chance and cause is closer than it seems.

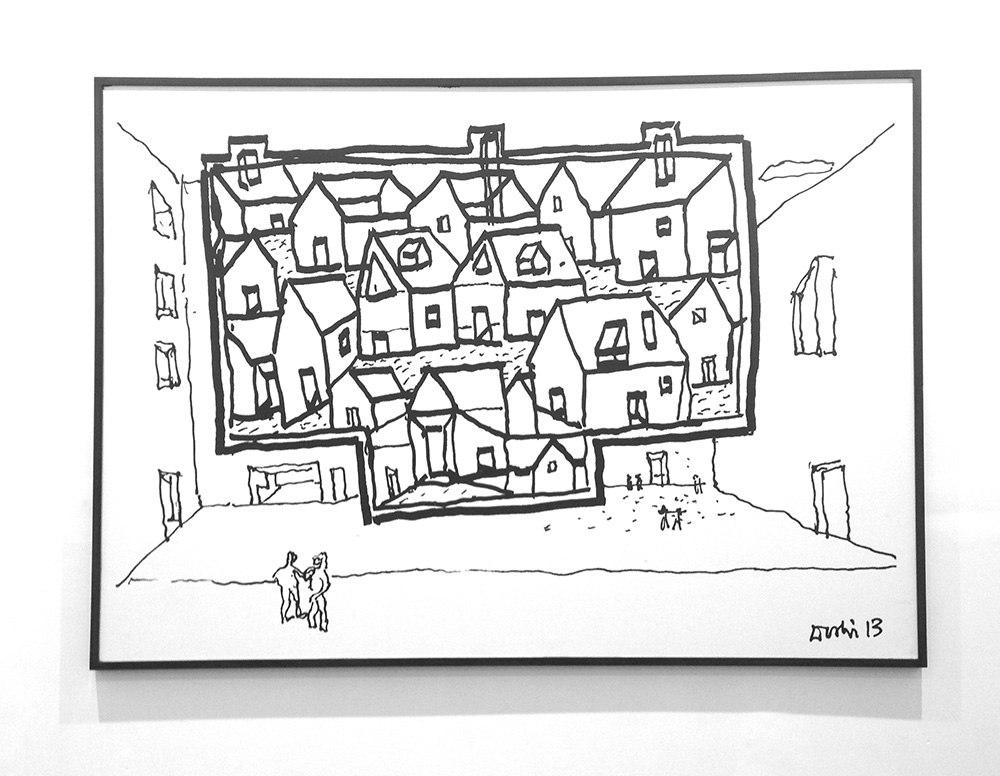

With the title The Forms of Life, the Life of Forms I want to invoke the idea that life has different forms just as forms have different lives and, at the same time, that the architect’s job is to give life to forms therefor forms to life, creating spaces in which life can take place under the best possible conditions.

Generally, of architecture we take into consideration the visible result, but the real result is not so much or only the appearance, but its effectiveness in the dynamics in and around the architecture.

Little is said about virtues, values, and merits such as variety and plurality or such as unpredictability. This last is considered an accident and a defect to be avoided in the same way as disorder, which is in truth the order whose logic is not given to be understood, that which is unknown and sometimes remains mysterious and impenetrable.

This is not a digression, I am referring to Doshi‘s ability to welcome the adaptation of his buildings to the needs of the inhabitants by the inhabitants themselves. An action that necessarily modifies and de-forms the initial arrangement. Well, Doshi was proud that the modifications sometimes made almost unrecognisable Aranya‘s dwellings, a settlement that is the result of a participatory design and construction process.

I remember when I spoke about him and his spiritual stature to Gino Veronelli, that he was a great all-round intellectual with whom we did not only talk about food and wine. It was to Gino that I owe the discovery of Edward Said’s book Orientalism, which gave new eyes to my travels in the East and challenged my previous approach, which was conditioned by Western-style optics. He told me that everything having to do with the religious and spiritual sphere did not belong to him. I should have expected this from a man with his feet firmly rooted in the earth who rejected dimensions other than the sensible ones as a refined cultivator of the tangible, the perceptible experience, the caress of taste.

That time he wrote to me:

Your words both spoken and read disquiet me.

An opposite result to what is your propose.

God is the other, is the only complete statement of an anarchist.

The road of subversion has no alternative.

My feeling was exactly opposite, I was talking to him about the usefulness of pacifying in oneself and with the Self, the pleasure of enjoying pauses and inhabiting silence, consequences of the amazement provoked by my encounter with illness and another me.

Doshi’s presence on earth was “a divine blessing, a gift”, as my sister Radhika sagely says in Premjit Ramachandran‘s 2008 film DOSHI, with various testimonies.

In mine I would only say that he had taught me to be myself. He helped me a great deal with his amiably inquisitive manner, already because with him it seemed to return to the Delphic motto of know yourself so dear to Socrates; the individual introspective knowledge he helped initiate did not elide the social and spiritual one by making the interior perceive itself as one with its surroundings. Talking with him was like walking on stairs with steps of varying heights, up and down, challenging work that made you climb up high, where you found yourself without hardly realising it, and then a moment later descend inside, into the depths of itself.

Doshi was an authentic in-segnante (that in Italian means teacher by combining “in” that is inside and “segnante” that is signing), leaving a mark inside, planting a seed that grew despite you and then blossomed and fructified. Teaching was never a one-way exercise for him but a back and forth with the interlocutor, he would question then raise.

He listened and seemed to learn in turn from everyone, looking for uncharted waters in which to bathe. You said something and immediately receive the satisfaction of feeling considered by a giant and at the same time carefully listened by a simple, direct, lovable person. After a pause he would then regularly add “and?”, taking up what you had just said, took you by the hand and led you further along a path that was never linear but sinuous, curved, circular, concentric, spiralling. That was how your horizon widened. He practiced the art of dialogue with rare mastery, as it must have been in the school of Athens.

While I am aware that non-presence is not absence, I immediately feel his absence strongly but since Doshi took every opportunity to celebrate, I too want to conclude by celebrating the joy of the miracle we are given to live, that vital space that lies between the wonder of birth and the enchantment of death.

Hari OM tat sat

Giovanni LEONE