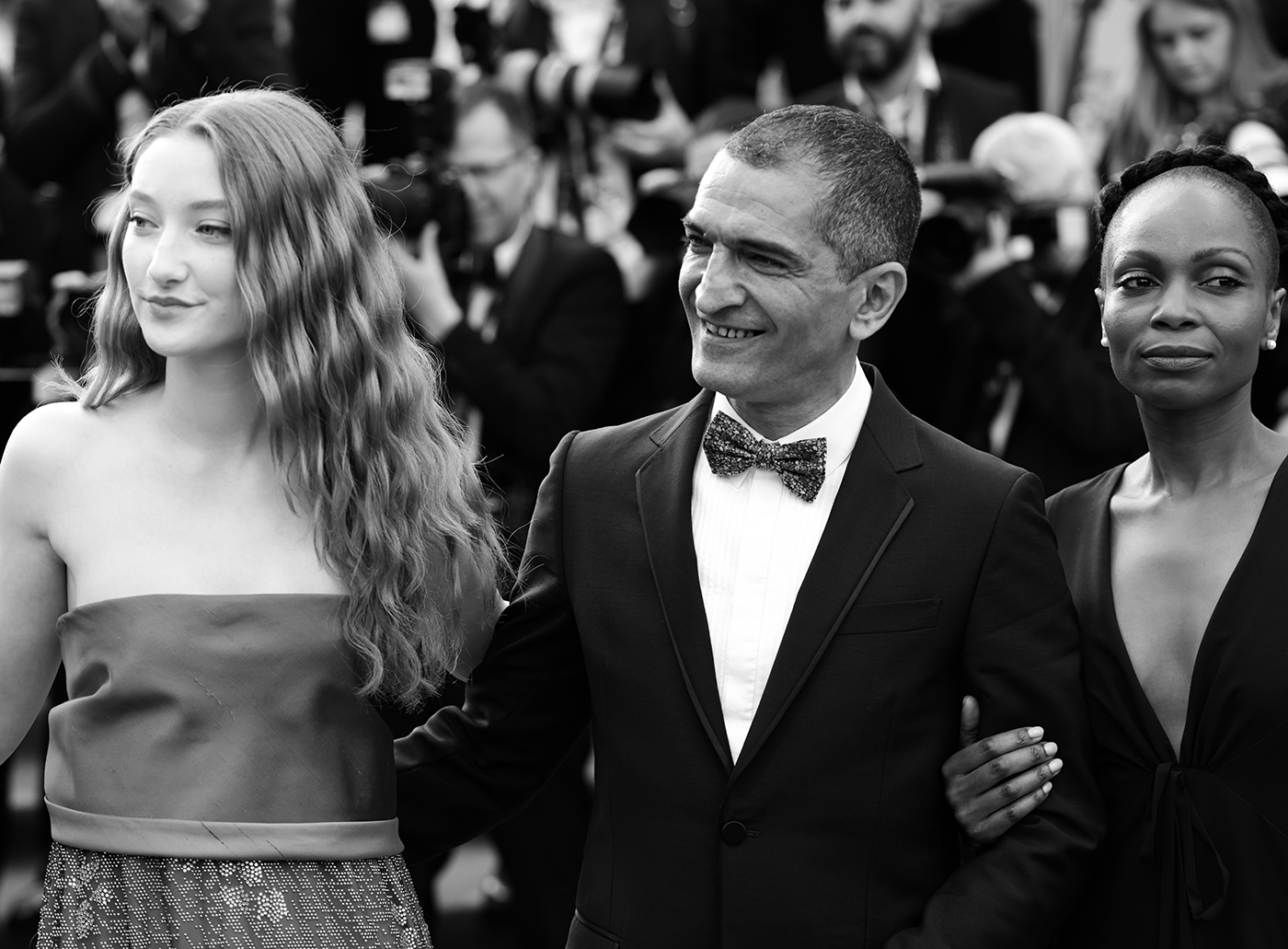

Four years after winning the UN Certain Regard Prize for “Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão,” Karim Aïnouz once again delves into the message of féminin empowerment, this time with a melodramatic biopic, presenting his first feature film at Cannes.

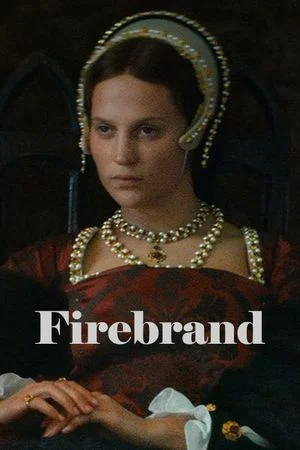

From the beginning of the film, he prepares us for an opening towards history, the one with a lowercase “h,” the story rarely captured by chroniclers of the time. While Henry VIII remained a superstar, dark and tormented character, it is rare that we take an interest in his unfortunate victims, his six wives. Karim Aïnouz draws inspiration from Elizabeth Fremantle‘s novel, “Queen’s Gambit,” released in 2012, where the British author depicts with great detail the troubled life of Catherine Parr, played by Alicia Vikander. Between love and tyranny, manipulation and conspiracies intertwine at the Tudor court, where the last wife of King Henry VIII navigates like a tightrope walker between life and death, and moreover, between Catholicism and Protestantism. A suitable setting to shed light on this character who can be part of feminist history, yet romanticize and even argue for the atrocious acts the director presents to us.

At first, the film is unsettling. The particularly contemporary dialogue is accompanied by an equally historical setting that, with a very realistic chromaticism, gives us a sense of a television film. But the camera’s gaze captivates us, with a clearly pictorial aspect employing chiaroscuro that can be called manneristic, and thanks to the talented performances of the cast, we can finally immerse ourselves in the story. It uses a contrast where we can highlight the stylistic simplicity. The portrayal of the female characters exudes a captivating freshness, particularly exemplified by the remarkable presence of Junia Rees as Princess Elizabeth. Conversely, Jude Law flawlessly embodies the repulsive nature of Henry VIII, who is depicted as both figuratively and literally putrid. This stark contrast between the luminous and vibrant future symbolized by the young Prince Édouard and the stagnant, oppressive patriarchal court further reinforces the prevailing sense of immobility within the narrative.

This film is to be appreciated frame by frame, not to say some sequences are brilliantly constructed by Helene Louvart. We salute Jenny Shircore for the hair and makeup, the lighting designer, and Michael O’Connor for the rooted work on the costumes. Yet we are left with an almost cardboard cutout romantic sensation. But if you reintegrate this movie into a history of feminism, never previously illuminated, the film can be applauded in this regard. Just as the social perspective illustrated by the queen’s childhood friend, Anne Askew, played by Erin Doherty, a Protestant preacher who abandons her status to open the eyes of the ignorant or illiterate masses.

Alexandra Mas

photos Cannes 2023 © Marco Tassini