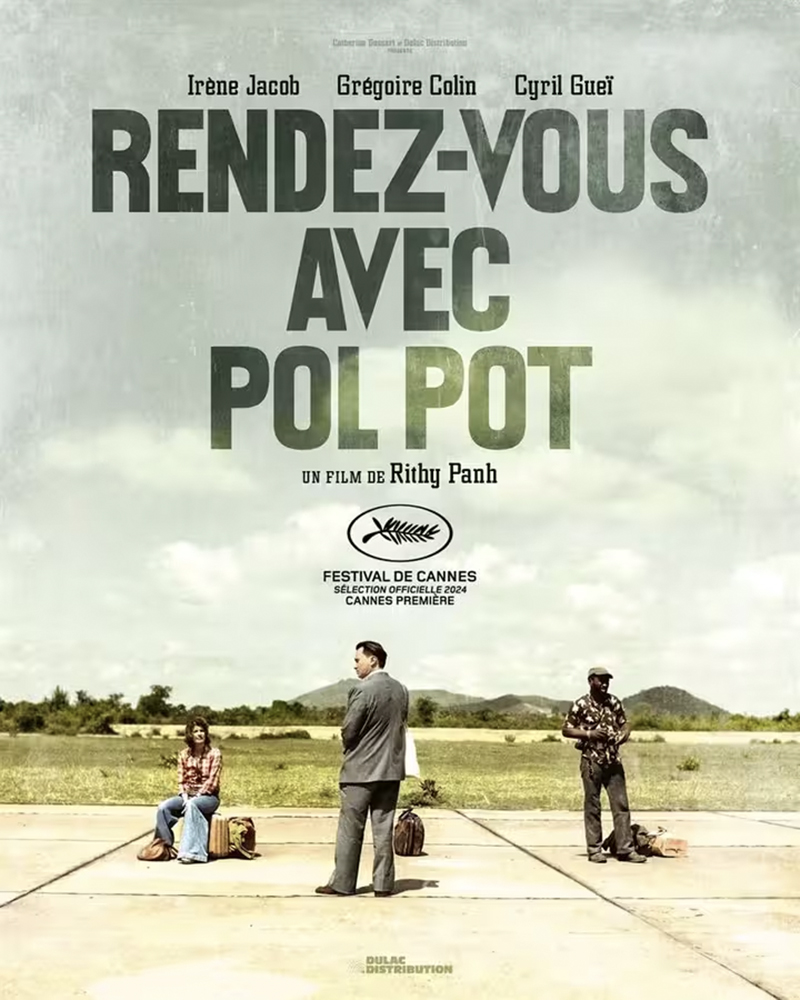

by Rithy Panh

with Irène Jacob, Cyril Gueï and Grégoire Colin

Cannes Première, Cannes Film Festival 2024

How Do You Document a Painful Memory?

Rithy Panh, is a Franco-Cambodian director known for his documentary work. He presented “Meeting with Pol Pot”, a feature film in the Cannes Première section. Feature or documentary, how do you keep alive the memory of a horrifying time? Rithy Panh feels a profound duty to remember again and again the tragedy that befell his country. This movie is loosely inspired by the book “When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution.” by American journalist Elizabeth Becker, one of the few Westerners to have experienced the murderous madness of a radical ideology implemented in blood by the Khmer Rouge and their leader Pol Pot in Cambodia between 1975 and 1979.

The Setting: Cambodia, 1978

In 1978, Cambodia, renamed Democratic Kampuchea, is under the control of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Nearly two million Cambodians have perished in a genocide that remains concealed.

The Story Through the Eyes of Three French Journalists

The film follows three French journalists: Paul Thomas, a photographer (Cyril Gueï), Lise Delbo, an experienced journalist (Irène Jacob), and Alain Carillou (Grégoire Colin), a professor and intellectual, a leftist militant, and former college friend of Pol Pot. They are invited by the regime to refute the scarce but damning information emerging from the country, which depicts an atrocious dictatorship.

How do you depict the silence of a people reduced to forced labor, the extreme pain of a mass fratricide where over two million disappeared for a pure Marxism devoid of any humanity?

The film explores the terror, abuse of power, famine, and death, all concentrated in a deadly silence. How do you film the unfilmable, the infamous reality of a communist regime driven to its darkest extremes?

The depiction of the three protagonists through their radical lenses is fascinating. Meeting “Brother Number 1,” Pol Pot, is a dream for his old comrade Alain Carillou. An idealist and communist militant, he passionately believes in the righteousness of the regime and the absolute possibility of building a just and egalitarian society.

Paul Thomas represents another type of idealist, one where journalistic freedom knows no bounds—it is an absolute fact and right. Rebel against the regime’s control reminiscent of “Potemkin,” where every detail is controlled. His need to reveal the truth goes beyond reason and fear. He is hunted and killed after managing to slip a film roll into his colleague’s typewriter.

Lise Delbo plays a special role, constructed as a tribute to the resistance fighter Charlotte Delbo. She is the only one to return from this inferno.

How do you depict the silence of a people reduced to forced labor, the extreme pain of a mass fratricide where over two million disappeared for a pure Marxism devoid of any humanity? The director employs a technique he experimented with in “The Missing Picture.” The film blends classic fiction scenes, archival footage, and sequences featuring sculpted and painted figurines, frozen like totems of pain and indignation, to illustrate what was never immortalized but is engraved with the blood of Cambodians in their ancient homeland.

For Rithy Panh, this is a personal story beyond that of his nation, it is through the pain he experienced as a teenager that he became the tireless engraver of Cambodian memory.

The Ideological Imposition

The Marxist ideology’s imposed clean slate demands the total disappearance of the individual in service to society and the common good. Torture, murder—”The people want blood,” explains Pol Pot. “It is better to imagine the absence of man rather than an imperfect man,” he told his horrified friend.

The Consequences of Extremism

The adhering and criminal extremism replaces the ideal of the people with absolute fear. In his enormous palace, typical of communist tyrants, Pol Pot brings his former colleague and friend to personal despair. Despite his efforts to hide the truth—clearly illustrated by the director with a hand covering the camera lens—his intellect refuses to believe in the atrocities, clinging to an idealization, as many did, ignoring the horrific realities of communist countries. Seeing his former friend decomposed by this reality is worse for the tyrant than responding in bureaucratic language to the journalist, who, as a woman, he does not regard highly.

The director skillfully infuses poetry into this horrific world where children are used or brainwashed by propaganda and classes of torture are given. The need for hope is urgent, and he offers us a symbol :. a pristine white staircase, like the skeleton of a futile ascent, appears several times. It leads to an unseen plane, toward a void, on a runway in the middle of nowhere where pain and fear reign. This aesthetic contrast effectively symbolizes a utopia that aimed to be beautiful but remains forever a senseless one.

Alexandra I. Mas

photo © Marco Tassini