photos and text Dr. Marco Tassini

Behind the overflowing ashtrays and with that grand piano being endlessly shifted, Maria Callas, La Diva, grants her final TV interview. She moves restlessly through the rooms of her Paris apartment, feeding her poodles, while visibly worn out from years of medication. The interviewer, aptly named Mandrax – after her preferred drug – sets up and checks the microphone. “I’d like to walk with you through your life,” he says, by way of introduction.

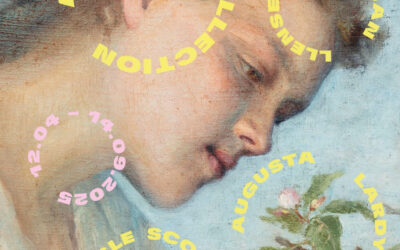

Callas’s life was a journey that took her from the slums of Nazi-occupied Athens to the world’s greatest concert halls, through a tumultuous romance with Aristotle Onassis, and high-profile collaborations with Pasolini and Zeffirelli. But Pablo Larraín’s sumptuous Maria smartly zeroes in on her final days, offering us Angelina Jolie as a regal yet crumbling figure, a lioness in winter. Retired for four years and increasingly fading into myth, Callas remains a living legend. “Make me an appointment with a hairdresser who doesn’t speak,” she commands her ever-devoted staff. “Book me a table at a restaurant where the waiters know who I am.” She craves, in her own words, adoration.

The film may be about Callas, but it is also about Jolie. Larraín casts her not just for her talents, but for what she represents: a former Hollywood icon now viewed through a lens of faded glory, much like the diva herself. Jolie is photographed like a relic to be examined, a statue to be revered. The fact that she trained for months to sing the pieces in the film, blending her voice with Callas’s, will likely attract attention. But make no mistake – her casting is as much about her own legend as it is about her performance.

Maria unfolds with a deliberate, stately pace, gliding through the highlights and heartaches of the diva’s life. Along the way, it pauses to acknowledge Onassis, played with gravitas by Haluk Bilginer, and briefly sits down for a coffee with her elder sister, portrayed tenderly by Valeria Golino. But the film remains primarily focused on Callas as she drifts through her apartment or strolls in the Jardin du Luxembourg, with 1970s bourgeois Paris providing a rich, evocative backdrop. This Paris, untouched by student revolts or the energy of the Nouvelle Vague, becomes its own character – an elegant, almost complacent setting that mirrors Callas’s fading world.

In some ways, Maria feels like the culmination of Larraín’s trilogy on wealthy, isolated women trapped by their public roles. Following Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021), this film continues his exploration of women who, despite their apparent power, are deeply imprisoned – both by societal expectations and the men who dominate their lives. The common thread is always the death of a powerful man or the end of a significant relationship, which heightens their isolation within these grand, oppressive spaces.

At the heart of Maria is the subtle tension between Callas’s desire to let herself die and the efforts of those around her to keep her alive, albeit in a gilded cage. Her loyal servants, played by Pierfrancesco Favino and Alba Rohrwacher, try to prevent her from fading away, with their adoring lies and gentle manipulation. Ferruccio (Favino), her butler, calls the doctor against her wishes, while she retaliates with requests that burden him emotionally, like having him move the piano. They are loving jailers, perpetuating her existence in a life she finds increasingly unbearable – as Maria, but no longer “La Callas,” the legendary figure her mental projections and others still address her as.

“There’s a theatre in my head,” Maria often says, and this film, too, is a stage, from the first to the last scene. The curtains rise and fall, mirroring the doctor’s remarks that everything is about life and death – but in the theater, both are real and yet somehow an illusion.

As with any great work of art, Maria risks being a glorious disaster. And yet, it revels in this uncertainty, keeping a fragile thread of pathos throughout. It’s as grandiose and unwieldy as that infuriating piano, but therein lies its power. This is theater, cinema, and life, all coexisting in a delicate, poignant balance. And by the end, like any good opera, it leaves you craving an encore.

from the EDGE print issue no VI